Nullification, Tariffs and the Lessons Learned from 1832

Posted on March 13, 2018

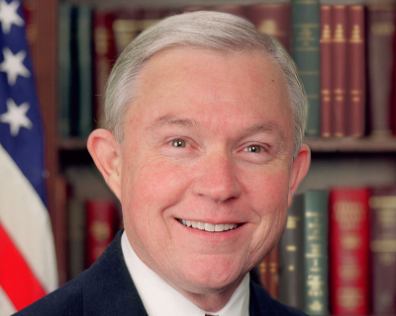

Attorney General Jeff Sessions

Last week, Attorney General Jeff Sessions accused the state of California of trying to nullify federal law by its continuing refusal to cooperate in the prosecution of criminal illegal aliens. In a separate development, President Trump announced that he was going to slap higher tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum.

Talk of nullification and higher tariffs brings back memories of 1832 when the issues were joined in what should be seen as America’s first constitutional crisis.

Andrew Jackson, President Trump’s role model, played a central role in the drama, as did Henry Clay, a hero to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). So too did John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun.

Clay’s American system, an effort to boost domestic manufacturing by increasing the tariffs of cheap English imports, by spending federal money to build roads and bridges and by creating a Second National Bank, didn’t sit particularly well with Andrew Jackson.

Jackson was ambivalent about the tariff, hated the National Bank, and more importantly, really disliked Henry Clay, who he blamed for the “corrupt bargain” that kept him out of the White House in 1824.

South Carolina was a big exporter of cotton and other agricultural products and despised the higher tariffs that came from the so-called American system. Starting in the aftermath of the War of 1812, Congress passed a series of increasingly higher tariffs that ended up in 1828’s final “Tariff of Abominations,” signed into law by President John Quincy Adams, who clearly was protecting manufacturers from his home state of Massachusetts.

Adams would subsequently lose the presidency to Jackson and, showing the relative power of the Congress back in the day, would return to the House of Representatives, where he would end up drafting the compromise legislation that would help to solve the nullification problem.

South Carolina, chafing under the higher tariffs, basically told the federal government to go stuff it. They weren’t going to enforce federal law, they weren’t going to collect the tariffs, they were going to be free-trade and free themselves from the bondage of the Congress.

John C. Calhoun, who was elected to serve as Jackson’s vice president, was so concerned about the nullification fever overtaking his constituents (and convinced that he wasn’t going to succeed Andrew Jackson as president) that he resigned and returned home to serve as the Palmetto State’s most distinguished senator.

Ultimately, the Congress relented on its high tariffs but did not relent on its supremacy over the states. It passed, at the urging of President Jackson, the Force Act of 1833, which stipulated that the president could use the military to force South Carolina to collect the federal tariffs.

This episode in American history is worth a reexamination, especially in the context of today’s debate.

What stopped the country from slipping into Civil War in the Age of Jackson was not the basic issues of state sovereignty and economic competition, because those issues remained unresolved until General Grant accepted General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

What kept the country from an earlier civil war was the ability of rivals like Clay, Calhoun, Jackson, Adams, and Webster, to get over their intense personal dislike for one another and hammer out compromises for the good of the country.

Another point: Congress played a central role in resolving this dispute and famous national actors returned to both the House and the Senate to not only actively debate serious issues but also find important compromises.

Similarly, today’s Congress must play the decisive role in resolving disputes that linger on issues like immigration and trade. Presidents come and go, as do their executive orders, but only Congress can pass laws that endure beyond one administration.

Congress must step up to stop the willful and deliberate subversion of federal law, on things like “sanctuary cities” and the selling of pot, but it can only do that by finding a compromise among the political parties and the stakeholders.

Compromise is not a dirty word and it is essential to the full functioning of our democracy. And ultimately, Congress is the place where that compromise must happen.

(Also published in The Hill)