Making the Senate Work: What Mitch Learned From Harry

Posted on December 1, 2014

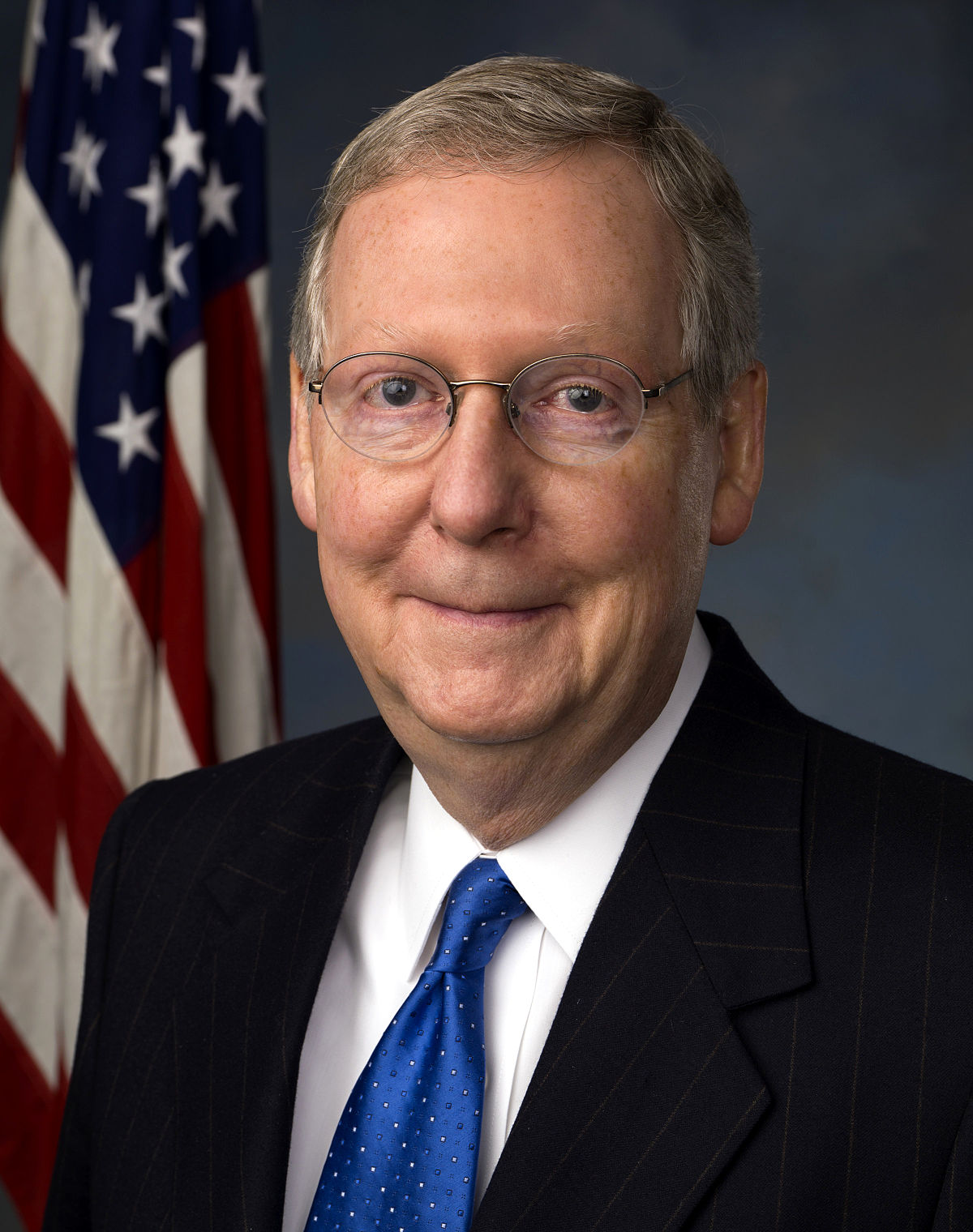

"Mitch McConnell official portrait 112th Congress" by United States Senate - http://mcconnell.senate.gov/public/?a=Files.Serve&File_id=1c0a32d2-9fb2-4321-8d7d-d9b3f0779bc8. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(This originally appeared in The Hill.)

Mitch McConnell has learned several things from Harry Reid about how not to run the Senate. Much to the surprise of his colleagues, he is going to apply those lessons next year.

First and foremost, he has learned that it is counterproductive to try to protect his members from tough votes. The greatest debating society in the world can’t function properly if it refuses to engage on real issues.

Under the Reid regime, the outgoing majority leader did his best to stop democratic debate from happening. He would “fill the tree,” which basically means he would make it impossible for his colleagues to offer amendments that he believed would reflect badly on the president or divide his caucus.Reid got unity all right, but through unity, he exposed his colleagues to another kind of vulnerability — many of them ending up voting with the president 97 percent of the time. In race after race, that 97 percent number played a critical role in helping the challenger beat the incumbent. That all happened because Reid didn’t give his members a chance to vote against the president.

Expect Leader McConnell to resist the temptation to fill the tree. Expect him to allow his colleagues to disagree with his leadership team on occasion, especially if they are in cycle and if they live in blue states.

Second, the incoming leader has learned that it pays to actually do the work of the Congress, which means considering spending bills.

Under the Reid regime, considering an appropriations bill was more rare than seeing a spotted owl. The Nevada Democrat instead used limited floor time to schedule message bills for the president’s agenda, like an increase in the minimum wage or the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, neither of which had any chance of passing the House. He also used plenty of time to force through presidential appointments. But allowing the Appropriations Committee to do its work held little appeal for Reid, because it diminished his power to get negotiate the final deals in an omnibus bill. Far easier to get your way as leader if nobody has time to read the big bill.

Expect McConnell to allow the appropriators to do their work. While earmarks are never going to come back in the same form as they once were, the new Senate leader was a late convert to their prohibition and he has the proper appreciation for the potential power of the spending committee.

Under the Reid regime, staff played an outsized role in the deliberations. Reid delegated much of the final negotiations to his chief of staff. News reports had that staff member actually arguing with the president in meetings and interrupting him on the phone.

McConnell has a good and very professional staff. But there is no doubt as to who is running the show in his office, and it is unimaginable that any McConnell staff member would personally engage the president in a direct and confrontational way. The Kentucky Republican has been described as his own legislative director because he is so engaged in every detail of the legislative process.

Some believe that the Senate is destined for gridlock, that it doesn’t matter which party holds the majority, that the institution itself is fundamentally broken. But that view tends to ignore the role of the key characters in charge.

What Mitch McConnell has learned from Harry Reid is that the Senate doesn’t have to function the way it has been functioning (or not functioning, as the case may be). It can return to regular order, where members are allowed to offer amendments, where party unity is not the highest value, where spending bills are regularly considered, where the senators are back in charge of the Senate.

McConnell is going to allow the Senate to function once again as the Senate. That won’t make everybody happy all the time, but hopefully it will restore a modicum of faith in the Congress.