Murder on the Orient Express and Judge Gorsuch

Posted on April 6, 2017

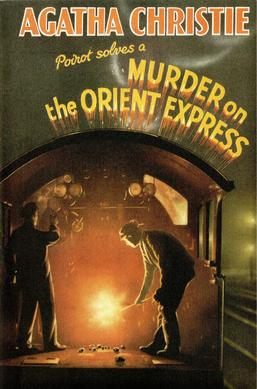

By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12993412

“Murder on the Orient Express” was one of the first movies that I remember seeing at the movie theater when I was a kid.

Based on the Agatha Christie novel, it was a classic period piece, with terrific actors and a winding plot. I don’t want to ruin it for you, but suffice it to say, outside of Hercule Poirot, the famous Belgian detective, everybody had a hand in killing the unsympathetic victim.

I was reminded of the movie and the novel this week, because of the murder in the Senate of one of its most cherished traditions, how the chamber goes about confirming Supreme Court Judges.

The Supreme Court is a political creation that theoretically is supposed to be apart from politics. It holds itself as the final arbiter of the incessant squabbling that occurs in the legislative and executive branches.

The Court makes its decisions based on voluminous research into legal precedents, by listening carefully to the arguments on both sides, by taking a pulse of what the American people think, and by coming up with the best rationale to justify their own opinions on the matter.

The Court itself used to meet in the U.S. Capitol building, on the Senate side, before moving to the gleaming white building that stands next to the Library of Congress.

The Supreme Court building is smaller than the Jefferson wing of the Library of Congress and if you add in the Madison wing, it is dwarfed in square footage. That gives you a sense of the relative power of the two branches.

I remember when several Justices came to meet with my former boss, the Chief of Staff to the Speaker of the House, to implore him to get them a pay raise.

Stalin once asked of the Holy See, “How many divisions does the Pope of Rome have?”.

The same could be said of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

His power is purely derivative. He and his colleagues rule and the hope is that his ruling our enforced by the other branches of government.

That is how it is all laid out in our Constitution and when all works well, that is how it all plays out.

The Supreme Court doesn’t get everything right. In fact, like many Popes in the past, their rulings have at times been spectacularly wrong, (ex. Taney and the Dred Scott decision, or Roe v Wade).

That means that what is settled by one Court is only settled for a period of time. Times change, opinions evolve, things get more complex, arguments get more refined, and sometimes, the Court reverses itself.

Those who occupy the Court are smart and have a long academic or political or judicial history that gives them the chance to get hired by the President with Senate assent to their jobs. But they are not infallible.

All a President can do is make the best case for his pick to the Supreme Court and hope that the Senate agrees with that decision.

We live in a very divided nation, politically. We also live in a very litigious society, where so many conflicts are decided by the Courts at all levels.

Our political parties have sorted themselves ideologically, geographically, racially, socially, emotionally, economically, and in almost every other way you can possibly think.

This sorting process has made the Supreme Court take on an outsized role in our lives and in our Constitutional process.

It is as if we voted on who would referee the final Championship game during the NCAA Final Four, and the North Carolina partisans had more votes than the Zag fans.

This isn’t really all Chuck Schumer’s fault, although he has played an oversized role in the downfall of Senate comity. As Josh Holmes points out in Politico today, it was Schumer who knifed Miguel Estrada in the front during his confirmation process to a lower Court because of concern that George Bush would elevate him to the Supreme Court.

Mitch McConnell is not exactly blameless either. After all, he was the one who constructed the Merrick Garland strategy, which I think was brilliant, ballsy, ruthless and exactly right. He had plenty of supportive comments from the like of Joe Biden and Barack Obama, who had commented in the past about how conservative jurists shouldn’t be given the time of day.

But neither McConnell nor Schumer do what they do in isolation. They don’t wake up one morning and decide, “Hey I am going to change a hundred years of precedent because I feel grumpy today.” They take these actions because that is what their constituencies and constituents demand.

Moderation is good in theory, but bad in political practice. Nobody gets elected anymore because of their effectiveness as a dealmaker (with the possible exception of President Trump). People get elected for standing up for their ideological principles and keeping faith with their ideology’s most radical proponents.

Until the American people decide that they want more centrist judges and more centrist political operators, we are going to continue down this partisan path.

It might be that the Senate never scraps its 60-vote rule for non-reconciliation items. But given the partisanship of the country, I wouldn’t be surprised if it did.

Who killed the filibuster rule? We all did.