The Good Veto

Posted on April 9, 2018

The only good veto is a nonveto.

That was the view of my former boss, Denny Hastert (R-Ill.), who served as Speaker of the House for six years of the George W. Bush administration.

Back in the day, the hard-right clamored for President Bush to veto a spending bill to show that he was fiscally responsible.

But Hastert was in no mood to be sacrificed at the altar of presidential expediency.

He would hold bills until most of Bush’s objections were resolved, making it difficult for him to make congressional Republicans the object of conservative fury.

The one bill that Hastert desperately wanted Bush to veto was campaign finance reform, legislation that proved to be a disaster for the political establishments on both sides of the aisle. (It turned out great for billionaires though.)

Ronald Reagan effectively used his veto pen to paint Congress as profligate spenders. But Dutch had a worthy opponent in Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill (Mass.). Tip was a profligate spender, and he enjoyed lambasting the Republican president’s heart of stone.

Sometimes congressional Republicans sustained the Great Communicator’s vetoes. But sometimes they didn’t, like when bipartisan majorities sent Reagan a transportation funding bill. It was after the Iran-Contra affair had broken, and the president was trying to prove he still had plenty of juice in Washington. But one man’s juice doesn’t win against many men’s demonstration projects, and the veto was overridden.

One of the reasons President Reagan was seen by most Americans as a tight-fisted spending cutter was because of these spending battles with Congress. He would veto, risking a government shutdown in the process, but to make the message stick, he had to have his team in the Congress with him.

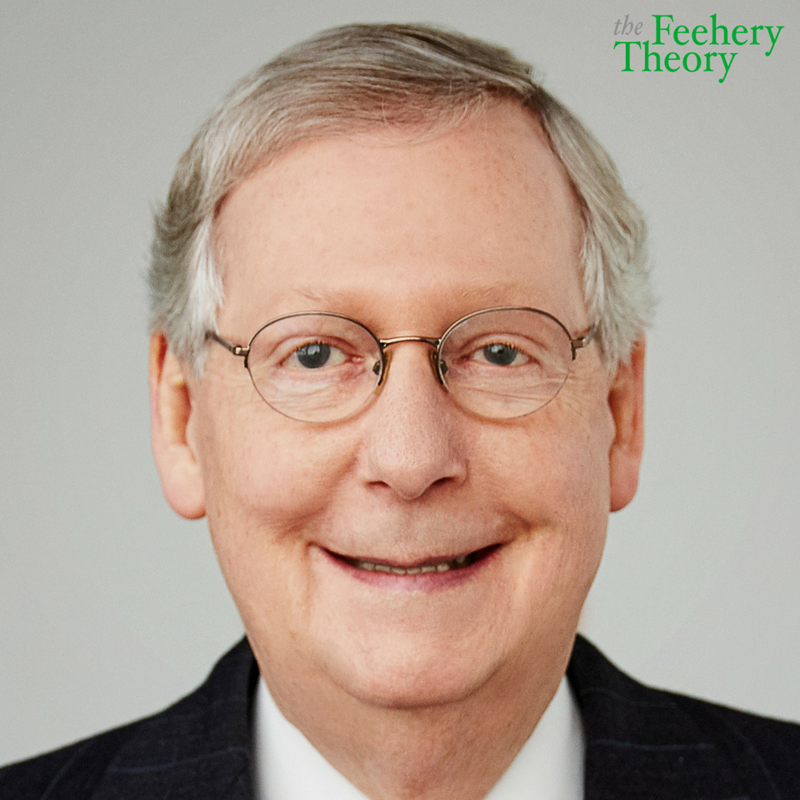

One person who wasn’t with Reagan on the highway bill fight was a freshman senator from Kentucky, Mitch McConnell.

McConnell has always been an institutionalist at heart and he knows a political ploy when he sees one. He didn’t like what Reagan did to the highway bill then, and it is unlikely that he will like it if the current president tries to pull a fast one now.

History has a weird way of repeating itself. When Reagan vetoed the infrastructure bill, Liddy Dole was the Transportation secretary, and her husband happened to be the leader of the Senate Republicans.

McConnell’s wife, of course, is Elaine Chao, who is the current Transportation secretary. There is very little likelihood that the president will put the McConnell family in the same awkward position that Reagan put the Dole family in, because there is very little likelihood that Congress will produce a veto-able highway bill any time in the distant future.

But should President Trump veto the next omnibus spending bill, it will likely be a point of discussion in the McConnell household.

It is rare that a president vetoes legislation produced by his own team in Congress, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t happen. Jimmy Carter vetoed 31 bills that came from the Democratic Congress, 15 percent of which were overridden. But Carter’s vetoes were evidence of a weakened president who had lost the faith of his own party.

For Donald Trump to win a veto fight over legislation produced by a Republican-led Congress, he needs to do the following three things:

- Identify clearly the red line that Congress can’t cross to gain his signature. Vague threats don’t work with either the public or with legislators. And if members feel they are being unfairly scapegoated, they will vote for their own interests over the those of the president.

- Find the right villain to vilify. Attacking fellow Republicans is counterproductive. It will not only deflate the base, making it more likely that Democrats take back the House. It will also turn friends into enemies, something the president really can’t afford.

- Make sure the public is on his side. It’s not hard to win a fight against a historically unpopular Congress. But if the president miscommunicates during a veto fight, comes off as erratic, inconsistent or unreasonable, he will lose the messaging war.

I don’t necessarily think that a presidential veto is the worst thing that could happen to Congress or to Trump. But it could backfire in spectacular fashion if not done with careful consideration and smart strategy.

(Published in The Hill)